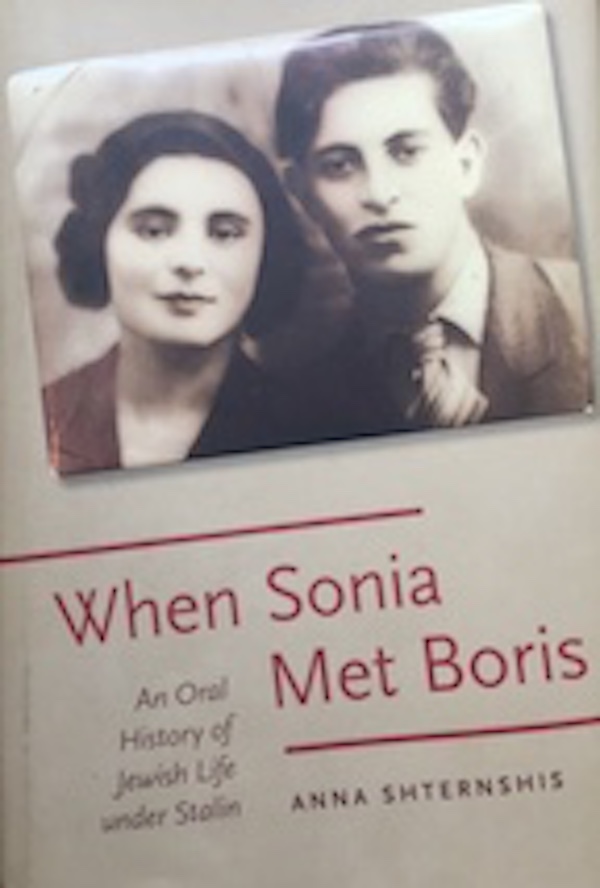

When Sonia Met Boris: An Oral History of Jewish Life under Stalin by Anna Shternshis, Oxford University Press 2017, $29.95 hardback; ISBN 978-0- 19-022310-6, 247 pages.

In October of 2013, the PEW Research Center published results from a survey on Jewish culture in the United States that unequivocally pointed to a shift in American Jewish identity. Like other religious groups, the survey suggested contemporary American Jews are less religious, less engaged with their community, and more open to intermarriage than previous generations. It also suggested that 40% of American Jews believe having a good sense of humor is as essential to Jewish identity as caring about Israel; and more than 30% think you can be Jewish even if you believe Jesus was the Messiah.

Increasingly, it seems, American Jews disassociate Jewishness from Judiasm: putting greater emphasis on (often arbitrary) markers of ethnic roots than religion; exhibiting the same kind of “thin identity” as the population for whom that term was first coined: Soviet-born Jews. If the correlation holds water—and I, for one, believe it does—then Anna Shternshis suggests the interviews in When Sonia Met Boris: An Oral History of Jewish Life under Stalin can be read as a kind of foundational myth for this new Jewish identity: “as unexpected, but valid, narratives of the birth of new definitions of what it means to be a Jew” (193).

Over a course of ten years, Shternshis conducted nearly 500 interviews with former Soviet Jewish citizens who were adults by the 1940s. Organized according to theme, When Sonia Met Boris offers a topical, kaleidoscopic portrait of the lived experience of the various facets of Jewish Soviet life: including marriage, education, employment, and migration, each of which is then subdivided according to decade. Her analysis is woven through the text to contextualize their testimony, adding historical dimension to conversations about how they made choices, raised children, and navigated housing policies, as well as educational and professional quotas—all parts of Soviet society for which there was no written record.

The greatest strength of the book, however, lies in Shternshis’s soft but steady focus on the semantics of her interviewee’s testimony, particularly her analysis of the various and changing meanings of the word “Jewish.” Depending on the context, the narrator, the country they’re from, their current circumstances, and the language they’re using, Shternshis shows how the word can serve as a stand-in for a whole spectrum of different words, including “good,” “bad,” “traditional,” “chaste,” “cheating”—sometimes within a single interview. By charting these shifts, Shternshis effectively constructs an intersectional map of the complex changes to Jewish identity over a course of decades in a repressive, nominally atheistic state.

Her conclusions are refreshingly modest. Instead of trying to summarize the Soviet Jewish experience in a single narrative, Shternshis offers an alternative course of inquiry: a generational examination of Soviet Jewry, using testimony to demonstrate just how very different the experience of one generation can be from the next. She’s also careful to identify the many potential factors that may influence the testimony, and explains how these forces may be affecting the data.

Although I’m certain the book can be read without a significant background in Soviet history, like any great oral history work, it is probably most useful for those who have one. After all, Shternshis is contributing to ongoing historical conversation and therefore employs a kind of shorthand for some of the most famous events in Soviet history—not all of which precede explanation. Mere mentions of the Doctor’s Plot, for example, which are littered throughout the book, serve to evoke an image, or a turn, or a crescendo in the conversation; the way “Auschwitz” or “Egypt” might, in a larger conversation about Jewry.

When Sonia Met Boris is nevertheless relentlessly useful, both for those who study Soviet history as well as for those who study identity. For those in that second category, like me, the book contributes to a larger conversation about whether or not this “thin” Jewish identity can exist without anti-Semitism, without associative misfortune. About whether or not it can be meaningful as Jewish. “Unexpectedly for scholars, and inconveniently for Western Jewish community leaders,” Shternshis concludes, “the answer is unapologetically ‘yes’” (193).

Emma Courtland is a graduate of Columbia University’s Oral History Masters program. She has worked as a writer, film programmer, and exhibitions curator for periodicals and nonprofits in her native city, Los Angeles.